Interview with painter Eri Robinson

In which we discuss disrupted realism, plein air painting, the creative process, and Bruce Lee

Eri is a painter living in Van Nuys. Right now, he’s been focusing on plein air painting— which, simply put, is the act of painting outside.

I met Eri at a house show my roommates and I posted. We got to talking about the creative process and I found myself very drawn to his view of art. We sat down at a café recently and had a great conversation about art. I hope you enjoy.

You can find more of Eri’s work on his Instagram and website. He’s also accepting commissions and inquiries, so feel free to contact him on Instagram or his website if you’re interested in that, or if you’d like to learn how to paint or draw!

This interview has been edited for clarity.

I guess the best thing to start with is what brought you to be a painter? How did you know this is what you wanted to do.

Well I’ve always drawn and painted since I was like a little kid, I guess. I can’t remember a time when that wasn’t what I wanted to do. Like I was saying the other night, I don’t really believe in “talent.” The idea of being born with talent is detrimental to creating good artwork or becoming a good artist, I guess.

So you felt like you were kinda born with this desire to—

Yeah, it was more like a compulsion. Like I was drawn to it in a way. but, if I hadn’t spent years developing that through lots of practice then I wouldn’t be at the level where I am today. So I prefer to think of it as a skill rather than as a talent because skills can be learned and developed whereas talent you’re born with. It’s given to you by God or some kind of divine intervention.

Did you go to art school?

Yeah I went to a small arts school. And I went to an arts high school as well. LACHSA. LA County High School for the arts. But I dropped out my freshman year and then got my GED when I was like 16 and started art school around then. Graduated when I was 20.

What was the art school called?

It’s called LAAFA. LA Academy of Fine Art. Very small school. There were like 10 people in my class when I first started and then 4, including myself, when I graduated.

Why did people drop out?

You know, financial reason or they had to move back home because their parents didn’t want them to be artists. Like my friend Rok, who’s from Thailand. His parents didn’t want him to be an artist so he moved back to Thailand.

He came all the way from Thailand?

Yeah a lot of people in my school came from other countries, actually. Very international kind of school.

Do you think that exposed you to some different mindsets about art?

Yeah, definitely. That was one of the best parts of my school was being surrounded by people from other cultures. Learning from them, not just because they were from other cultures but people who were dedicated to learning about art and knew a lot about art and we would exchange different ideas and look art together in a different way than most people would.

Was there any sort of global art style you were drawn to?

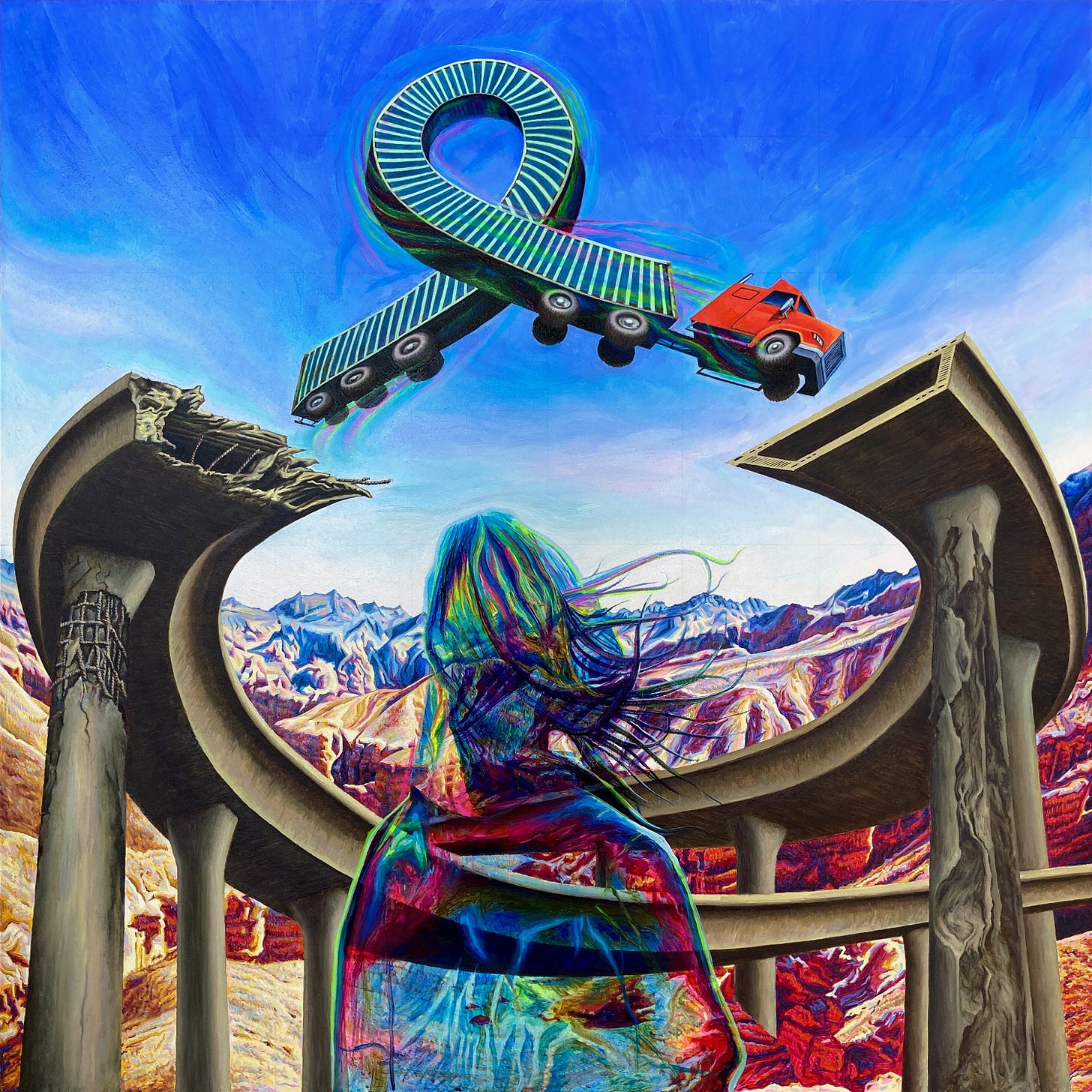

Yes, I guess so. I mean, there’s not really an exact term for it. I guess you could call it disrupted realism. But that’s not a very common name. Or maybe Neo-baroque could be another word for it. It’s kind of hard to describe but it’s this movement of realist artists who have the kind of skills of realism to do very realistic portraiture or landscape work. And they take that work and they’ll destroy it a little bit. They’ll make something photorealistic, like a photorealistic portrait, and they’ll burn it a little bit or throw acid on it. So there’s this kind of juxtaposition of creation and destruction within the work. Both abstract and figurative realism. Where it’s like combining all of the different movements of the 20th century in a way. Where it’s both conceptual and realistic in a way. It’s exploring ideas found in abstract work and ideas that are found in realistic work as well. So I feel like that is kind of the next level, in a way. It’s very post modern. Because post-modernism is kind of a free for all, in a way, where you can take things from any different time period and combine them. It’s just kind of a mish mosh, a pastiche, if you will, of all kinds of different things. Like Quentin Tarantino, the way he takes combines all kinds of different references from all kinds of different movies.

Yeah, I’ve been thinking about post modernism a lot, actually. Because it’s a hard term to define because across different disciplines it can mean a lot of different things. But I think the thing that helped me understand it the most is the absence of an over-arching narrative that can describe all of our lives. It used to be in the western world the church was the overarching narrative of people’s lives.

Yeah, and then Nietzsche comes along and says “God is dead. Culture must replace God.” [laughs]

Right, and I guess he was right. I mean post modernism is kind of a testament to that.

I kind of love that idea that art and culture should replace worshipping God in a way. Because it gives us power, in a way. Believing in God is kind of letting yourself be dictated by this higher power, whereas if you believe in art and culture, then you believe in humanity and yourself. Not in an egotistical way but in the fact that humanity has enough to itself to just believe in itself

Right. So what is your weekly or daily routine look like for painting? Is there a time of day you typically work or is it kind of on a weekly basis you find time for it?

Well I try to work everyday. But, I don’t know, sometimes it’s hard to find the time. I don’t know. Life gets in the way.

I know that.

I don’t know. Different things. But I try to do at least one painting or drawing every day. Because if I don’t then I’ll kind of become a little stale or I’ll be rusty little bit when I try to get back to it if I don’t do it every day. So there are some days when I’m not really making a finished piece. I’m just drawing for drawing’s sake so I can keep my skill level.

Keeping the blade sharp.

Yes, exactly. Like I got to a lot of uninstructed workshops. It’s basically like a figure drawing class but without a teacher. There’s a nude model on the model stand and there’s a bunch benches around with artists with their pencils and paper. It’s called like an art horse. I don’t know if you’ve that before. It’s like a wooden bench with a place for you to rest a drawing board on. It’s kind of a mixed group. A lot of people are either amateurs or hobbyists. Some are professional artists who work in animation. Others are fine artists. Some are students. It’s kind of like a community art class that’s like fifteen dollars. You just pay a fifteen dollar entrance fee for the model. And it’s like three hours of figure drawing, starting with some two minute poses and then some five minute poses and then tens and twenty five minutes. So it’s nice to practice drawing that way. You can’t really beat drawing from life. Drawing from photographs can be useful but I feel like drawing from life, I get something more personal out of it. It’s more personal to my experience

And what about drawing from memory?

Right, uh, drawing from memory can be tough. I feel like sometimes drawing from memory can make things idealized, in a way. Drawing from memory and drawing from imagination are kind of like the same muscle in the brain. If you want to draw from imagination you have to practice drawing from memory. But that’s not really the kind of artist that I am. I’ve found that I prefer drawing from life, generally. Because I really appreciate realism. That’s something that I’m drawn to. And honesty. There’s like a truth to what I see, in a way. And translating that truth into a visual medium.

That sounds interesting to me because our memories and our imaginations, they have this idealizing factor to them. Life is always disrupting that. So what you imagine is always going to be— even if you remember it perfectly, life from one moment to the next is totally different.

It’s like when you remember something you can rewrite that memory in your mind. Like maybe you had some sort of argument with your friend and originally you thought you were in the wrong— but then later on when you remember that memory, you change it and say “Oh I was in the right.” [laughs] You can edit your memory in that way. So it’s kind of similar to how, if you were to try to draw something from memory, you might draw differently from how it actually was. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. That’s just not what I’m searching for right now.

So for your non commissioned work— just work that you’re making for yourself— it would be great if you could walk me through that process. Starting from the first inkling of an idea of the first marking on the page to finishing the work and then sending it out.

I mean my process has changed a lot over the years. I used to have a much different process than what I do now. I guess at the start I try not to over intellectualize it because that can be damaging to my creative spirit. I try to just follow my instinct. Because I’ve learned to develop my intuition. I’ve honed my intuition so that I know what I want to do without having to really verbalize it.

So would that instinct start with: you’re in front of a canvas and an inkling of an idea comes and you try to execute it? Or do you just make a mark on the page and then make the next mark on the page and then let it develop from there?

It depends what I’m doing but recently I’ve mostly been doing plein air work so let’s start with that. So if I’m doing plein air painting I decide I’m going to go to a spot. Like let’s say I’m going to go to a waterfall in Eaton Canyon. And yeah I’ll pack up the car, get there, unpack the car, hike to the spot I’m thinking about. And then I’ll look at the spot from a bunch of different angles— or I’ll just wander around until I find something that really inspires me a lot. Like “Wow, I really want to paint that.” Or something that draws me in— that resonates with me about that subject matter. And then I try to hold onto that initial inspiration throughout the whole process of the painting. Where I try to keep that spark or flame alive. Because it’s kind of tough to hold onto that feeling. If you don't do that right away when you have that instinctual reaction to it, sometimes you lose that and you lose the motivation behind the piece. If you don’t perpetually, consistently hold on to that.

Reminds me of a lot things in my own work but we’re not here to talk about me.

You wanted the whole process. So that’s sort of the start. That’s the initial inspiration. So I’ll go to a spot, see something that catches my eye, set up, do some painting. And then, depending on the complexity of the piece— how much detail I want in the painting or the complexity of the subject matter— like, this waterfall painting took me a long time to make because water is very tricky to paint. So I’ll either paint in one session— maybe three or four hours— and do a whole painting if it’s more simple in that time. Or I’ll go back to that same spot multiple times for multiple sessions on the same painting. This waterfall painting took me about four or five sessions working between six and eight hours each day. And I had to wait for the weather to be the same because I started the painting when it was overcast. And so I had to go back on an overcast day. Which is actually easier to paint that kind of lighting scenario because the light remains consistent throughout the whole day. A kind of diffuse lighting. Versus painting when it’s sunny out, the sun moves across the sky so the light and shadow moves very quickly. An hour later, it’s a totally different scene. When I’m plein air painting over the course of several hours on a sunny day, the painting ends up being a combination of several different day times.

That’s tricky, yeah. So when the work is completed where does it go?

In a pile. [Laughs]

And on your website.

I haven’t updated my website in a while, actually. I’ve been trying to build a new body of work that I haven’t really released much of yet. I’m trying to do that this next year where I’m entering into a few competitions and an artist’s residency and trying to get into this magazine called Plein Air Magazine as well. They have some competitions. So I’ve been trying to build this body of work until I have a lot of it. And then I’m gonna start posting more of it on my instagram and on my website. I’ll show the work sometimes at different events. Like I did a show a few months ago in a park in Highland Park. My friend Sean and Paige organized this event where it was a bunch of vendors musicians, different bands and artists, who were putting on a show together in this park. A suggested donation sort of thing. And I was one of the vendors. I had a table set up with all my paintings. I sold a few pieces that way. I don’t really have gallery representation right now. But that’s something I’m working towards. It’s kind of tricky choosing what gallery to apply to. Like, is this really the right fit for me? Are they going to promote my work and sell my work? Are people going to see it enough through this gallery or is it just gonna sit in the gallery? There’s a lot of different factors. And then there’s a lot of competition to. Plenty of people out there who are doing good work, even better than me or about the same level as me. They also want to get into those galleries. And [the galleries] will take forty or fifty percent commission so I’m a little hesitant to enter into that kind of arrangement. Right now, if I sell I painting I get paid the full amount for it.

So it’s a question of whether it’s worth it for the resources that they could provide.

Yeah. But it would be nice to have people see my work that way.

Right. I’ve been struggling with reach as well.

I’ve always been more focused on making good work than promoting and selling it, honestly. That’s been kind of my weakness is the business side of things but I’m trying to get better at that these days. I like teaching because it feels more honest, in a way. Whereas art— it’s kind of hard to sell because it’s a commodity and not a necessity. So it always feels like you’re accepting a generous donation from someone when they buy your painting [laughs]. So, it’s like “Will you please buy my painting? I know you don’t need it but could you buy it?” [laughs] Whereas teaching it feels like an honest exchange of services where I’m teaching them a skill they can use, which is a little different than just selling a painting that they don’t need.

Little change in topic. You spoke to me about tai chi. Could you give me a quick summary of your background in tai chi and how it has influenced your work?

Well I started doing kung fu and tai chi when I was around 21. I’ve always been inspired by Bruce Lee, actually. He was a big influence on me when I was in school. One of my teachers in school used to say all these Bruce Lee quotes to us when we were drawing and [we would apply] these ideas of Bruce Lee’s to painting. Like “Be like water, my friend.” And the concept of flow. I think the concept of flow can be applied to any art form, especially. Music probably the most. But there’s flow in drawing and painting as well. Or people call it “the zone.” Like “you’re in the zone” in sports, maybe. If you’re a runner— you’re just like Usain Bolt running to the finish line or something. He’s just in the zone in that moment. Truly present. And it’s kind of like tapping into a different type of consciousness. It’s like your subconscious or something. Something that Carl Jung talks about a lot. The unconscious, and tapping into that. And your unconscious works faster than your conscious mind because it’s more instinctual, in a way. Kind of like back to that instinct I was talking about earlier in the painting process, where I try not to over-intellectualize it at the start because that can dampen the creative energy. I analyze the way I did the painting later on. But at the start I don’t want to think about it too much. I just want to follow my inspiration.

So, yeah, thinking about Bruce Lee— I’ve just been very inspired by Bruce Lee and he actually went to school for philosophy when he was in college. And he wrote a book about philosophy, which I have, and his philosophy of martial arts called feet kune do, which means “Way of the intercepting fist.” And so yeah I started doing kung fu when I was like twenty one and I loved it. It was great. I did it for about two years and then I stopped going to classes because I was going through a lot of stuff at the time with my job and with— I don’t know. I was partying too much doing a lot drugs. It was just too much trying to balance my crazy partying lifestyle and working full time and trying to do kung fu too. So kung fu kinda fell away from my life at that time. But I recently started up again. My old kung fu instructor hit me up and was like “Hey, you wanna come do kung fu in the park in Burbank on Wednesdays?” and I was like “Hell yeah I wanna do that.”

That’s great.

So I started doing that a few months ago. And I would do some tai chi here and there just on my own just to stay in shape and as sort of a moving meditation. But it wasn’t a regular disciplined practice the way I was doing it in my early twenties.

Everything you’re saying about flow and instinct— that’s kind of why I practice meditation: to help me maintain that inspiration while working on a piece. The idea of the unconscious— or the subconscious, whatever you want to call it— from what I understand the dominant model of the human mind right now is that there’s the unconscious and the consciousness is just the very tip.

Like the ice berg.

Yeah, it’s a filtering mechanism for understanding and putting a narrative around all the chaos. And when you’re working on an artistic piece you wanna lessen that filter so you can expose yourself.

Yeah, you’re trying to tap into that. Let’s say you’re playing baseball. You can’t intellectualize when you hit a ball. It’s a physical thing. It’s intuitive. So your unconscious mind is doing all the work. It’s making all the calculations in a micro second so that you’re swinging the bat correctly in that moment to hit the ball correctly. You’re not thinking “Oh I’m swinging it at this thirty degree angle” or whatever. It’s happening so fast that you can’t intellectualize it.

Also on the topic of meditation and being like water— one thing I’ve learned from my meditation is the art of letting go. Letting the thoughts come and letting the thoughts go.

Yeah we were talking about Ekhart Tolle. And he has this metaphor where it’s like your thoughts are like a dog that you’re walking and the dog is sniffing different things, chasing it, but you don’t have to follow that dog. You’re just holding onto to the leash. So basically you are not your thoughts. They are like a separate entity from you. You can just watch the thoughts as they go by.

Yeah, or one metaphor I really like is your mind is an ocean and your thoughts are the fish swimming through the ocean.

Oh, that’s good. Very David Lynch. Waters a great metaphor though. Beneath the surface of the ocean there’s so much. The subconscious.

But trying to apply this skill of letting go— I’ve being trying to apply this skill of letting go to my work in certain ways. I guess it’s mainly trying to strike the balance between putting enough effort and energy into a piece and then when to say “Okay, I have to step away from this. I have to let it go for a little bit so I can come back to it with fresh eyes, having the well of my subconscious been refilled.

Finding a center, in a way. You recenter yourself so you can come back to it with a fresh perspective. Because sometimes I feel like I can bogged down by the weight of the work. Not that it’s strenuous work but in my mind, sometimes I just need to let go of that and come back to it with a different perspective. Oftentimes, looking at the work in a mirror helps that. Because you see it in a totally different way.

I wish I could do that with my writing. So how can you tell when the best thing you can do is to step away from it for a moment and return.

Yeah, that’s tough because it’s easy to overwork things and take things too far. Like sometimes I think I should have stopped working on this painting like half an hour ago. I fucked it up. You know? [laughs] There’s too much detail or something. It was better when it was more minimalist. Sometimes less is more.

Have you developed a skill for getting that eye when you’re like “Okay, no more work on this.”

Yeah, I mean it’s kind of hard to define. It’s again that intuition, where I just developed my intuition to this point. Also, something that’s helped with my intuition is consuming so much painting and visual media. I spend so much time looking at art and trying to understand art and memorizing paintings that I love. And I’m trying to understand what it is about them that resonates with me to the point where I have this visual library in my mind that’s built up over years and years. And it kind of works as a filter, where I filter through different things that I perceive and think about: “How can I translate them in a way that will be resonant?” That’s kind of abstract.

Well I mean that’s how I’ve developed my own instinct. The books that I’ve read have shaped my unconscious in ways that I can’t intellectualize. I can’t actually describe.

For sure. You’ve just internalized [them] and it’s become intuitive for you. That kind of filtering mechanism.

Yeah. Okay, I wanna push on this idea a little bit more. Because my worry for myself is— what I have trouble telling is: is my instinct telling me “It’s time to take a break from this work?” Or is my instinct just being lazy. Where it’s actually I just want to go drink coffee and eat breakfast and scroll through twitter.

No but sometimes that’s good to do because, you know, our body and our mind are not really separate. We tend to think that they are but if you’re body isn’t working then your mind isn’t working either. So sometimes it’s very healthy to just take a break and just live and come back to it with fresh eyes. And yeah, it’s important not to beat yourself up about that too. Like, we all need to just take a break and step back and, I don’t know, eat some food. Sometimes I’ll forget to eat if I’m painting for like four or five hours straight. I’ve done a painting and think “Oh, shit, I need to eat now. Or I need to use the bathroom. I need to pee really badly and I didn’t realized until I just stopped painting right now.”